The Odium Epidemic

To the soul that harbors it, it is both stimulant and venom

There are few activities in this world that are more wholesome or uplifting than watching small children play with one another.

Despite the occasionally chaotic action or egocentricity driven by a limited worldview, the character of children possesses a purity and simplicity where every action is both intentional and without guile. When they play together, it is so they can play, together. When they hurt each other, by activity or accident, they remediate their differences and life carries on. They harbor neither grudge nor animus, and forgiveness is quickly rendered unconditionally, save for continued social engagement.

Wherever you go, whatever the culture, small children are all the same. Yet the passage of time eventually leads to the twilight of childhood innocence, ultimately replaced by a character constructed upon choice, experience, and perception. While preservation of those early virtues would be wonderful, there is an inescapable transition in adulthood. By comparison, adulthood is a complicated jumble of awareness and action. The world expands along with our emotions, complicating our once simplistic worldview. But despite that complexity, those emotions, most of them, can serve as a useful tool to shape, build, and guide the world we come to know.

Most of them. There is one amalgamated emotion — a blend of fear, disgust, and ruminated anger — that inhabits multiple contexts and erodes whatever it touches. To the soul that harbors it, it is both stimulant and venom. Everyone (eventually) is capable of it, and everyone who nurtures it, is eventually eaten by it. It promotes both survival and extinction. It is the antithesis of childlike virtue.

You know it more formally as hatred.

A New Epidemic

The present-day odium epidemic doesn’t marshal any scientific declarations, in part at least because there’s no real way to quantify it. Anger, we can and do measure using scales like the STAXI-2, or aggression, through the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Hatred is more difficult to pin down given its complex makeup and contextual dependence. For simplicity’s sake, we can think of it as excessive and unrestrained anger.

Despite not having any fanfare, the odium epidemic is a very real phenomenon with potentially catastrophic ramifications on both a personal and social level. We may not be actively measuring it, but there are arguable changes in the American culture that point to something new. Boundaries appear to be realigning. The Overton window of public discourse admitting new dialogue that was once collectively dismissed. The world has frankly been full of suffering and pain, and even with the advent of technology allowing us to see more of this suffering at once, in real time, it feels as though something has broken.

There was once a time when the willful and malicious taking of an innocent life, meaning murder, was routinely disparaged. The details of the victim’s life were not evaluated for sympathy, and circumstances never permitted justification. Now, it may either be scrutinized for relevance, or even applauded.

When did an evaluation of a victim’s background become relevant in our condemnation of their murder?

A Personal Destruction

As public health takes interest in anything that alters outcomes in human health, it may come as no surprise that there is a rather extensive research examining the relationship between measured anger and health.

What may surprise you (or perhaps not) is that through repeated and rather robust measures, all the data report that anger kills you faster. Slowly, no doubt, but surely.

Here’s one example.

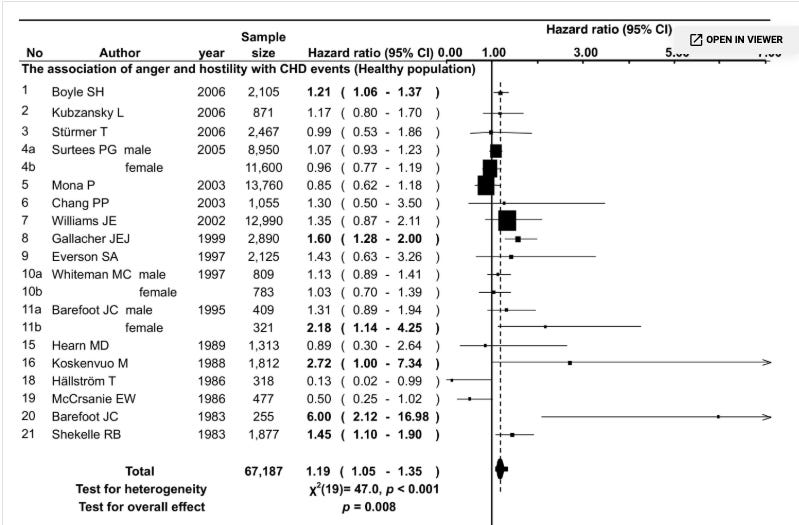

In a rather extensive meta-analysis that included data from 25 cohorts (totaling more than 70,000 people), researchers compared various levels of anger and hostility with reported new cases of coronary heart disease (CHD). Participants were followed for long periods of time, often longer than 10 years. Among otherwise healthy populations, individuals reported to consistently express anger or hostility more often had a 19% greater chance of being diagnosed with CHD by the end of the study period. Among those who were already ill, the effect was worse, at 24%.

It carries on, in various populations, for various conditions. In patients dealing with hypertension, those who reported the poorest anger control were 35% more likely to experience either a fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular incident. Over a 20-year period, being frequently angry meant you had a 17% greater chance of dying from heart disease, even when controlling for various confounders.

It brings new application to the phrase, “Poisoning the heart”.

A Social Decay

Anytime you have large groups of people living together, you are likely to experience additional threats to mortality. That’s not doom-predicting. It’s simple data. Each individual life carries on within its social circles, pursuing its own interests and engaging its communities. However, conflicts inevitably rise with so many distinct interests and personalities. People value different things, or pursue different ends, and sometimes these inevitably cross paths. At times our personal decisions will have effect on the collective, and when that happens, there will be tension that is either legal or cultural.

For example, consider the tension between an individual’s right to express their conscience, and how their communication influences the actions of others. In America, you are legally entitled to express your opinion without reprisal, so long as your expressions are not illegal calls to action or in violation of contractual agreements (such as may exist with employers). Indeed, you can hate someone, and tell them such. But such expressions would not exist in isolation.

Consider the recent attacks on religious minorities within the United States. We see religious organizations targeted because of their faith identity. Men, women, and even children, killed at the hands of someone whose hatred became their compass, the only crime of the victims being the worship of their God. Entire congregation sites lit up in flame, by someone convinced they were doing a public service.

How does that happen?

It happens because the relationship of anger and health extends into the relationship of anger and action. People are much more likely to cross the boundary dividing words and action, if you anger them, and rally them behind a preexisting prejudice, whether that be directed at a person, a group, or an idea. From that lens, you may find yourself less likely to follow the rallying cry that goes, “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention.” If someone wants you angry on their behalf, they want you as an object.

All this is to reiterate how, yes, a person readily sits within their rights to refer to religious minorities “demons,” or “filth,” and even “deserving of [spiritual] destruction.” But consider, what will the effect of such expressions be on individuals who already sit close to the line of action? People who simply need an excuse, a rationale to hurt others?

In the wake of such attacks, it seems we’re more invested in reinforcing what you can say, not what you should say. We think of the rights of those who express their hatred, but not of the religious observers who nervously glance up every time someone opens the door.

Perhaps the worst part of this epidemic, the most entrenching quality it possesses, is that everyone who participates feels empowered by it. Everyone. For every reason. Expressions of hatred are a stimulant, intoxicating the user with a sense of moral superiority, reduced ambiguity, and deactivated empathy. Hating another person, when done for the “right” reason, just feels so good. At least in the moment. Drug addiction by contrast may stimulate the soul, but it leaves one ashamed and reclusive. Such is not the case for hatred, where we are so proud of it we’ll take to media to publicize it, or publicize it from someone who expresses it better than us.

It’s such a strange personal perception, believing you can out-hate your enemy, or that we can wield our hatred as a tool. So many people completely miss the point that they are the tool, and hatred is what does the wielding. That wielding takes on different forms; othering, signaling a threat, mischaracterizations, digging a pit, etc.

What is to be done?

As a simple suggestion, read this speech, Lincoln’s second inaugural address. It’s a stunning series of statements delivered at the height of the Civil War, where a nation was pitted against itself over the question of extending or diminishing the human slave trade.

Observe how Lincoln describes his enemies:

With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan ~ to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations

Consider the state of a nation which would appoint a leadership like this, which extends this much grace and exhibits this level of restraint. Herein you don’t find any clever quips, any focus on the soundbite. All you have is commitment to do good and give your enemy the benefit of the doubt.

We could use this. Again. Ultimately, the individual efforts which play out will continue to morph the culture, and whether or not the odium epidemic carries on as per usual is yet to be determined.

Just remember though. It does not have to. It doesn’t even require teaching or enforcing new laws or expectations.

It just requires us to remember something we all used to carry. Back when life was simpler, and the world was smaller to our vista. Where our actions were always sincere and our mercies quick to extend.

We did it once.

We can do it again.

Such thoughtful words. Thank you.

Exceptional piece. The cardiovascular data adds real weight to what most people treat as just moral philosophy. What stuck with me was framing hatred as both stimulant and venom, becuase that duality explains why people cling to it even when it harms them. We dont often connect our internal emotional states to physical outcomes this directly. The Lincoln quote brings it full cirlce by showing restraint is possible even at societys breaking point.