The Dramatic Gestures and Uncertain Impact of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines

There are indeed a few charming components, but there are also many questions regarding some of the more antithetical claims therein

The entertainment medium of the 90’s was unprecedented. Disney was dishing out the hits (now classics), Pokemon knowledge was a metric for social status among children, and Japanese anime became mainstream through show called “Sailor Moon”. The show featured the character Usagi Tsukino, who would transform into the titular heroine and fight evil alongside her fellow Sailor Guardians.

Aside from its endearing stories of kindness, bravery, and the banger-of-an-opening-intro (listen to it here), it had a character known as Tuxedo Mask, an ally of the Sailor Guardians. Rather than actually fight alongside the heroines, Tuxedo Mask would usually make dramatic entrances and talk to the Sailor Guardians at a safe distance from the actual battle. He’d offer obvious hindsight, make general commentary, and sometimes encourage the ladies. He never actually did anything, yet somehow he was always lauded as a mysterious and powerful figure within the show.

For reasons unclear, this sentiment felt familiar watching Wednesday’s White House press briefing for the release of the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs).

Reaction to the new DGAs has been mixed. Among dietitians and most healthcare professionals, the commentary ranges from “a mess” to “contradictory”, while avid supporters of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F Kennedy (RFK) Jr. were either ecstatic or disappointed.

Among the more thoughtful commentary about the new DGAs — the quinquennially released federal report that serves as the cornerstone on what and how to eat to promote health, prevent chronic disease, and meet nutrient needs across the lifespan — there has been minimal insight offered on the press briefing itself. While there’s plenty to glean from the 10-page 2025 DGAs (a major reduction from 2020’s 164 page report), or the 90-page science report… or its 418-page appendix, there is insight from both the press briefing as well as the reports.

Taken together, there are incongruous components of these DGAs which give rise to uncertainty regarding application, practicality, and approach to dietary implementation. There are indeed a few charming components, but there are also many questions regarding some of the more antithetical claims therein.

So first, the charm.

The most important, and likely under-appreciated (if noted at all) gem within these DGAs comes in the form of a 12-word statement:

… support American farmers, ranchers, and companies who grow and produce real food… [italics added']

It may well be that the most egregious oversight of all previous DGA reports is their failure to make this acknowledgement; the centrality of farmers and the work they do. There would not be dietary guidelines, nor the field of nutrition science at all, were it not for this fractious portion of the population that feeds everyone.

Previous reports which mentioned farmers treated them as downstream stakeholders, rather than central figures. That order is incorrect, and even though this nod of support is limited, it is explicit and extremely refreshing to see from the federal government.

Within the written text of the DGAs, there is plenty of material carried over from the 2020 version; similar guidance on fruit and vegetable intake, an emphasis on fiber-rich whole grains, and the regular consumption of dairy. They also detail how the advisable protein recommendation range is now 1.2 to 1.6 g/kg. Regarding this latter detail, that is welcome change. While data from national samples posit that most adults already consume at least 1.0 g/kg of protein, there is a strong case for an increase for the very range now advised within the DGAs, as described by researcher Stuart Philips within a piece published in The Conversation.

However, this is where the charm fades and the American public now wades into uncertainty and numerous questions given the report and press briefings inconsistencies, unusual assertions, and paradoxical positions.

So, thinking caps on.

During the press briefing, RFK Jr. is the first to formally introduce the new DGAs and he comes out swinging for the fences.

[We release] the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in history. These guidelines replace corporate-driven assumptions with common sense goals and gold-standard scientific integrity.

As the notes progress, there are additional alluring details noted, such as the promise to invest more into nutrition science through the NIH, or the assertion to coordinate with private health organizations. However, as things progress, it starts to adopt a more melodramatic tone, including RFK’s assertion that if a foreign nation wanted to cripple our economy or weaken our national security, it would do so by addicting us to ultra-processed foods.

But he goes further, stating that the federal government of the past intentionally acted to drive these changes to worsen the health of American citizens, and that corporate interests played a role as well, allowing policy to determine the science, and not the other way around.

So the tone is set for the unveiling. A total reset, based on “gold-standard” science, without the consideration of corporate interests.

Then, we see the pyramid…

Now to truly appreciate this, you need an inside joke among dietitians. It is a fact that almost every dietitian will say the following phrases at some point in the course of the week; 1) “It depends”, 2) “Nutrition is individualized”, and 3) “No, we stopped using the food pyramid back in 2010”.

We may need a new inside joke.

Speaking of which, RFK Jr. then gets back to business and outlines the rest of the dietary guidelines, and trades with commentary from others in attendance. The summary is as follows,

…eat real food.

This phrase is repeated throughout the conference (and within the DGAs), along with admonitions to consume more meat, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

But we then veer into unusual statements and assertions.

For example, RFK Jr. claims that these DGAs are the first to address ultra-processed foods. However, there’s a glaring detail that contradicts this statement. Nowhere within the DGAs is there any mention of ultra-processed foods. Instead, you have reference to “highly-processed foods”, and while most nutrition professionals can read between the lines, this is an interesting contradiction, likely attributable to the HHS failing to settle on an actual definition of ultra-processed foods, as they attempted over the summer of 2025.

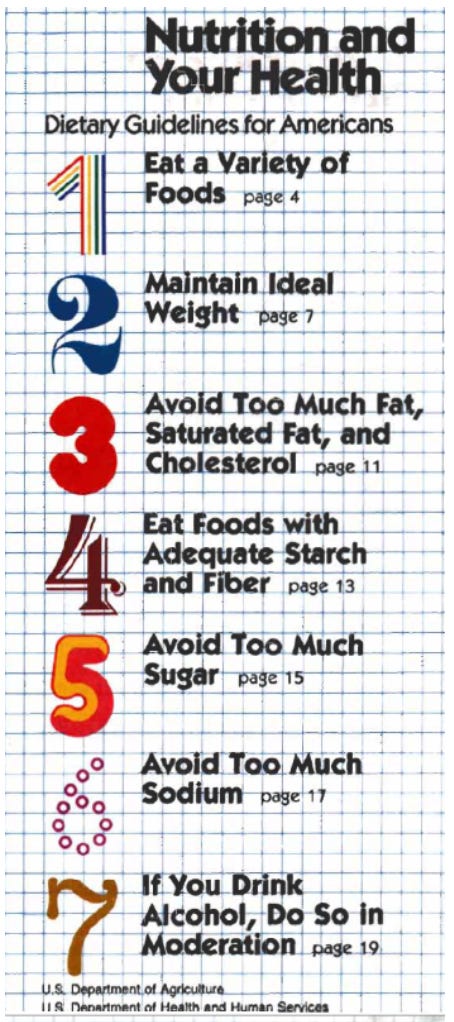

Amidst this great reset, there are many “Tuxedo Man” claims about how the current administration is finally advising against foods made up of refined grains or added sugar. But unless RFK Jr. intends for this great reset to be for 1980, the year the first DGAs were released, he is incorrect in his assertion because even back then with the limited data available, low sugar intake was advised (see item 5).

Gone are the recommendations that offer objective metrics for assisting with intake patterns, such as keeping at least half of your grain intake from whole grains, or to restrict added sugars to no more than 10% of calories. Instead, we have statements about the priority for “fiber-rich whole grains”, or that “one meal should contain no more than 10 grams of added sugars.”

For context, 10 grams of sugar is the approximate amount you’ll find in a standard BBQ sauce, but don’t expect guidance on whether the protein content of grilled meats negates the need for that limitation.

Speaking of which, meat stands out as the definitive winner of the DGAs, with a general priority made for protein at every meal. While plant-based proteins are named within the DGAs, they seem noticeably absent within the new inverted pyramid graphic, save for two walnuts, an almond, and what appears to be a peanut. Meat, meat, meat, emphasizing these as nutrient-dense and high-quality, with no admonition regarding leanness of cuts, or fat content. At some point in the press conference, meat was mentioned so often it sounded as though an orc had prepared the secretary’s notes.

Plenty of other dietitians have also pointed out the incongruity of the new recommendation to consume full-fat dairy (high in saturated fat), promote butter and beef tallow (also high in saturated fat), but retain the recommended limit to consume less than 10% of your calories from saturated fats. Apparently, this was seen as betrayal by many of the keto/low-carb advocates, causing them to clutch at their hearts, but hopefully not due to soft plaque buildup.

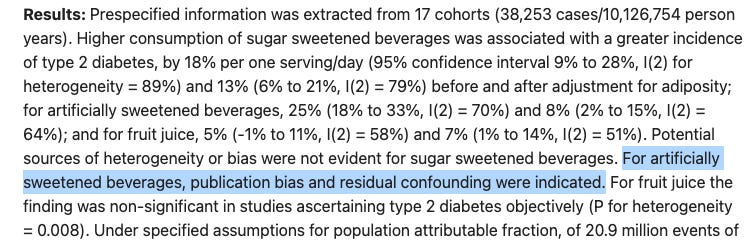

In one more major reversal from previous DGAs, non-nutritive sweeteners are targeted and treated as similar to added sugars, with recommendation to avoid them. This flies in the face of data that clearly demonstrates how when replacing sugar-sweetened beverages, non-sugar sweetened beverages (such as diet sodas lead to improved health outcomes. The report stakes this claim on the basis of seven identified meta-analyses assessing non-sugar sweetened beverages and various health endpoints, stating that there was a significantly increased risk (of moderate grade certainty) for all-cause mortality, changes in BMI among children, and Alzheimer disease.

The scientific appendices cite that the evidence for their claim is weak, but since it matches the literature they read on added sugars in sodas, non-nutritive sweeteners were lumped in. This is an extremely poor read of the present literature, as researchers now know that early studies failed to control for individuals who had already been diagnosed with health conditions (heart disease, diabetes, etc.), and then started drinking non-nutritive sweeteners. Even one of the meta-analyses cited in the appendix admits as much.

It also may be worth noting that the “rigor” of scientific quality seems to fray here, with numerous errors in basic study details, such as claiming how a cited study evaluates the effects of artificial sweeteners, when in fact, that study does not actually evaluate artificial sweeteners, as noted in the screenshots below.

Finally, and perhaps strangest of all, was the decision to downgrade advice on restricting alcohol intake. The new DGAs still discourage alcohol, but removed the objective limits that were advised from the previous edition.

Dr. Oz fielded the question from the press about advisement on alcohol, and he responded with:

Well, alcohol is a social lubricant that brings people together. In the best case scenario, I don’t think you should drink alcohol, but it does allow people an excuse to bond and socialize, and there’s probably nothing healthier than having a good time with friends in a safe way.

Now to each their own, but the framing here hardly sounds negative. In fact, this rhetoric mimics talking points from alcoholic beverage lobbies. Industry messaging from these lobby organizations know they don’t have a scientific edge, so instead, they often promote their product cultural or social cues. The Beer Institute has launched entire campaigns on the sociality of beer.

The phrase “social lubricant” was even the headline of a major article in the World of Fine Wine.

Frankly, it is hard to know what to do with these DGAs. There are many contradictions. There are many ambiguities. Worst of all, there are antithetical statements and administrative actions that are decisively and totally at odds with one another.

You cannot decry corporate influence driving the decisions from previous DGAs and seek counsel from numerous individuals with potential conflicts of interest.

You cannot encourage consumption of saturated fat and tell people to restrict it to less than 10% of their calories.

You cannot create a visual graphic that minimizes grain intake and maintain the same whole grain serving amounts from previous DGAs.

You cannot encourage calorie restriction and discourage consumption of zero-calorie beverages.

You cannot claim to be the great reset and offer more limited, weaker dietary advice already provided 35 years ago.

You cannot demonize highly-processed foods and added sugars to the American public and publicly enjoy a meal that consists of highly-processed foods and sugars.

So, for any dietitians who observe these contradiction and are asking the question, “How are we supposed to use these?”, there is a simple and clear answer.

Don’t.

It’s not the bible. It’s a set of recommendations, and if those recommendations fall short or fail to meet an appropriate standard of evidence, don’t rely on them.

It is, yet again, an opportunity to show the public the capability and evidence-based care of the dietitian.

Our admonition as healthcare professionals is to follow the best available evidence, in line with good clinical judgment, adhering to the desires of the people we serve. If any organization or administration is failing to do that, than the responsibility falls upon us to carry on, ask good questions, and provide appropriate services.

The 2025 DGAs made their grand entrance, offered their rhetoric, but will retreat from the hard work of providing clear, consistent guidance. The fighting, IE, the interpretation of evidence, the navigation of contradictions, and the application of the complexity of nutrition science in the real world, still falls to you.

But don’t be discouraged. It has ever thus been.

This was a sharp and frankly necessary read! The Tuxedo Mask analogy lands because the public briefing felt like certainty theater: big rhetoric about “gold-standard science”, paired with recommendations that become fuzzier (or internally inconsistent) exactly where clinicians need precision.

The core issue isn’t whether any single line item is “right”. It’s that dietary guidance only helps when it’s operationalizable: clear definitions, measurable targets, and transparent evidence standards. When the document swaps objective guardrails (e.g., added sugar/sat fat frameworks) for vaguer language, it pushes the cognitive burden back onto clinicians and dietitians, who then have to translate ambiguity into real-world decisions for patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, CKD, etc.

I also appreciate your emphasis on incentives and credibility. Nutrition is already a high-noise field; when federal guidance appears to mix messaging with politics, it erodes trust and trust is a health intervention. The practical “prescription” you end with is exactly right: follow the best available evidence, quantify absolute benefit/harms, and keep the patient’s context front and center. If the guidelines don’t meet that bar, clinicians shouldn’t be forced to pretend they do.

Well-said!